Robot Framework User Guide

Version 2.0

Table of Contents

1 Getting started

1.1 Introduction

Robot Framework is a Python-based, extensible keyword-driven test automation framework for end-to-end acceptance testing and acceptance-test-driven development (ATDD). It can be used for testing distributed, heterogeneous applications, where verification requires touching several technologies and interfaces.

1.1.1 Why Robot Framework?

- Enables easy-to-use tabular syntax for creating test cases in a uniform way.

- Provides ability to create reusable higher-level keywords from the existing keywords.

- Provides easy-to-read result reports and logs in HTML format.

- Is platform and application independent.

- Provides a simple library API for creating customized test libraries which can be implemented natively with either Python or Java.

- Provides a command line interface and XML based output files for integration into existing build infrastructure (continuous integration systems).

- Provides support for Selenium for web testing, Java GUI testing, running processes, Telnet, SSH, and so on.

- Supports creating data-driven test cases.

- Has built-in support for variables, practical particularly for testing in different environments.

- Provides tagging to categorize and select test cases to be executed.

- Enables easy integration with source control: test suites are just files and directories that can be versioned with the production code.

- Provides test-case and test-suite -level setup and teardown.

- The modular architecture supports creating tests even for applications with several diverse interfaces.

1.1.2 Screenshots

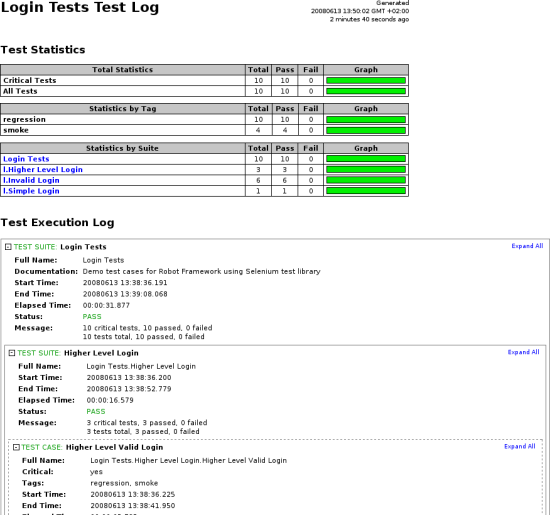

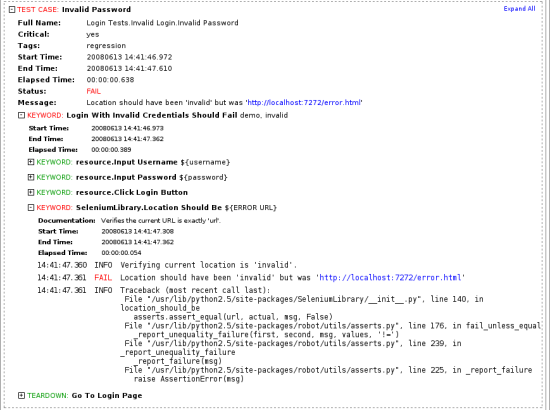

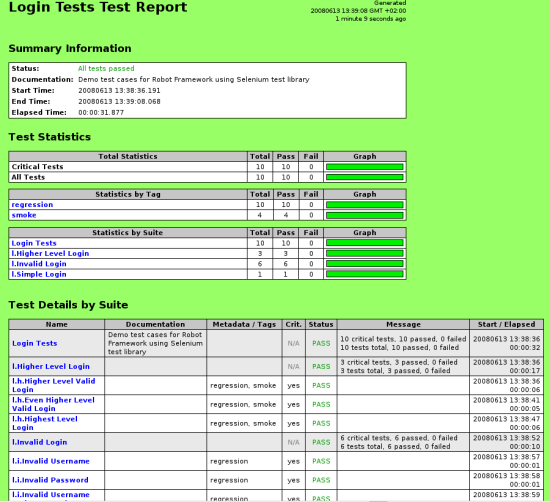

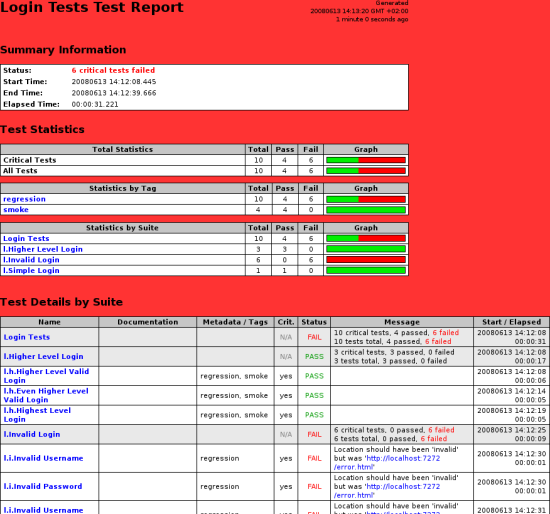

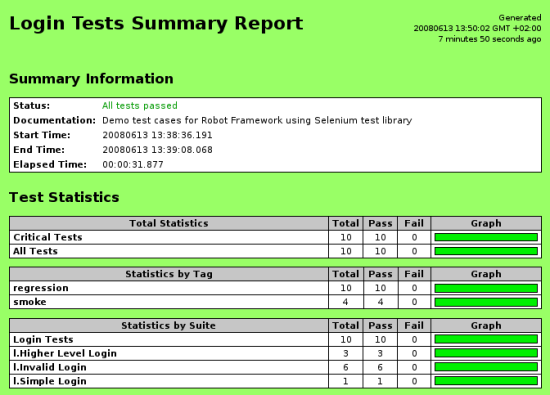

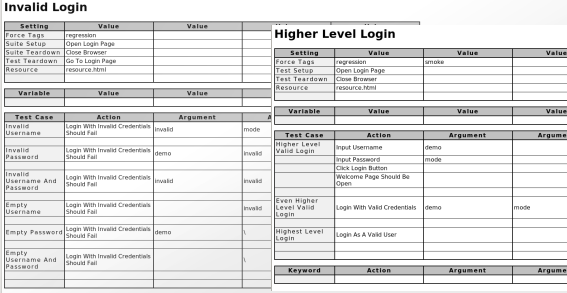

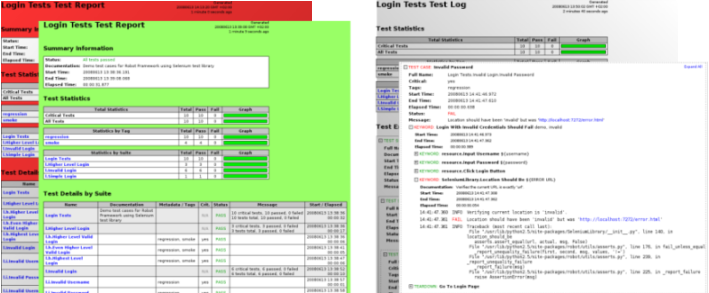

Following image shows screenshots of Robot Framework test data, test reports and test logs.

Example test case files

Example report and log files

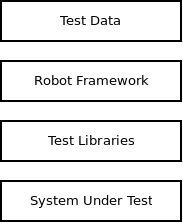

1.1.3 High-level architecture

Robot Framework handles the processing of test data, the controlling of test execution and the reporting of results for testing. The testing and interaction with the target under test is done by test libraries that are plugged into Robot Framework. Test libraries may internally use other test tools, but this is not visible to Robot Framework.

High-level architecture

As shown in the figure, Robot Framework's role in a test framework is to take test data, process it into a format that is appropriate for the attached test libraries, invoke the test libraries with the appropriate arguments, receive the data about the test from the test libraries, and then report it. The test libraries are responsible for interacting with the target under test.

1.2 Copyright and license

Robot Framework itself, test libraries and supporting tools distributed with it, as well as this user guide and other provided documentation have the following copyright statement.

Copyright 2008 Nokia Siemens Networks Oyj

Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 (the "License");

you may not use this file except in compliance with the License.

You may obtain a copy of the License at

http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, software

distributed under the License is distributed on an "AS IS" BASIS,

WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied.

See the License for the specific language governing permissions and

limitations under the License.

1.3 Installation and uninstallation

1.3.1 Introduction

There are two ways to install Robot Framework:

- Installing from source

- You can get the source code either as a source distribution package or directly from version control system. In the former case, first extract the package somewhere, and as a result, you have a directory named robotframework-<version>. Detailed instructions follow, but in short, what you need to do is to go to the created directory and run the python setup.py install command.

- Using binary installers

- Binary installers are platform-specific. There is currently only one binary distribution available, a graphical installer for Windows.

Installation packages are available from http://downloads.robotframework.org, and source code from http://source.robotframework.org.

1.3.2 Preconditions

Robot Framework runs both on Python and Jython, and you need to have at least one of them to be able to use it. However, the provided installers only work with Python, so installing it is always recommended.

Python installation

Python 2.5 is recommended, although Python 2.4 and 2.3 are also supported. On most UNIX-like systems, you have Python installed by default. If you are on Windows or otherwise need to install Python yourself, your best place to start is probably the Python homepage. There you can download a suitable installer and get more information about the installation and Python in general.

Note

The Python installation framework coming with Python 2.3 does not have functions for copying other than Python files. Robot Framework itself can be installed with it without problems, but, for example, installing certain libraries may require copying those non-Python files manually.

Jython installation

Using test libraries implemented with Java or using Java tools directly requires running Robot Framework on Jython, which then requires Java Runtime Environment (JRE). The minimum required Java version is 1.4, but newer versions are recommended, as they tend to be faster with dynamic languages, such as Jython. Both Sun and IBM Java versions are supported.

Robot Framework requires Jython version 2.2. The earlier Jython version 2.1 is not compatible with Robot, and also 2.2 betas and alphas have some problems and are not supported. Unfortunately, also Jython 2.2.1 has certain Unicode problems (for more information, see http://bugs.jython.org/issue1802339 and http://bugs.jython.org/issue1032), which makes it incompatible with Robot Framework. Hopefully these problems will be fixed in future versions.

Installing Jython is a fairly easy procedure. First you need to get an installer from the Jython homepage or directly from http://downloads.sourceforge.net/jython/jython_installer-2.2.jar. Note that the installer is an executable JAR package, which you need to run as java -jar jython_installer-2.2.jar. Depending on your system, the installer runs either in the graphical or the textual mode, but in both cases, the actual installation procedure is very easy.

When installing Robot Framework, its installer tries to find the Jython executable on the system to create the jybot runner script correctly. Jython is found if:

Jython can be executed in the system directly (i.e. it is in the PATH).

An environment variable JYTHON_HOME is set and it points to the Jython installation directory.

The Jython installation directory is found. On Windows, it is searched from the C:\ and D:\ drives, and on other systems from the /usr/local and /opt directories. The directory is found if it is under the searched directories mentioned above, or one level deeper. For example, the following Jython installation directories would be found by the installer:

C:\APPS\Jython2.2 D:\Jython22 /usr/local/jython2.2 /opt/whatever/Jython22

If you plan to use Robot Framework only with Jython, you do not necessarily need Python at all. In that case, you need to perform a manual installation or have some custom installer.

1.3.3 Installation

Installing from source

You can get Robot Framework source code either directly from version control or as a source distribution package that needs to be extracted somewhere. In both cases, you should have a directory containing the source code, documentation, tools, templates, and so on.

You should be able to install Robot Framework to any environment where Python runs using a source distribution. The installation is done by going to the created directory from the command line, and after that running either of the following commands:

python setup.py install python install.py install

setup.py is a standard Python installer script. It can take several parameters allowing, for example, installation into non-default locations not requiring administrative rights. It is also be used also for creating distribution packages.

install.py is a custom installation and uninstallation script for Robot Framework. When it is used for installation, it simply uses setup.py, and thus above commands are totally equivalent.

With both of these commands you get a rather long output, and something like the following text should appear at the end:

Creating Robot start-up scripts... Installation directory: /usr/lib/python2.5/site-packages/robot Python executable: /usr/bin/python Jython executable: /cygdrive/c/jython2.2b2/jython.bat (found from system) Pybot script: /usr/bin/pybot Jybot script: /usr/bin/jybot Rebot script: /usr/bin/rebot

Note

The paths vary based on your environment. Robot Framework uses the standard Python installation system and should operate in accordance with the host operating system conventions.

Using binary installers

Use the platform-specific way of installation. For example, on Windows, double click the provided executable and follow the instructions of the graphical installer.

Manual installation

If you do not want to install Python, or for some other reason do not want to use any automatic way of installing Robot Framework, you can always do it manually following these steps:

- Get the source code. All the code is in a directory (a module in Python) called robot. If you have a source distribution or a version control checkout, you can find it from the src directory, but you can also get it from an earlier installation.

- Copy the source code where you want to.

- Create the needed runner scripts. If you have a source package or a checkout, you can get templates from src/bin.

Where files are installed

When an automatic installer is used, the Robot Framework code is copied into a directory containing external Python modules. The actual location is platform-specific, but on computers with a UNIX-like operating system, it is normally something like /usr/lib/[PythonVer]/site-packages, and on Windows it is [PythonInstallationDir]\Lib\site-packages. The actual Robot Framework code is in a directory named robot.

Robot Framework runner scripts (pybot, jybot and rebot) are created and copied into another platform-specific location. On UNIX-like systems, they normally go to /usr/bin and are thus immediately available from the command line. On Windows, the operating system does not provide a similar natural place, and Python copies these scripts into [PythonInstallationDir]\Scripts.

Setting up environment

After the installation, you might want to make Robot Framework's runner scripts easily available from the command line. On UNIX-like systems, that should be the case automatically, but for example on Windows, it is not. In environments where startup scripts are not available, the directory containing them must be set to the PATH environment variable.

Setting the PATH environment variable on Windows:

- Open Start > Settings > Control Panel > System > Advanced > Environment Variables. There are User variables and System variables, and the difference between them is that User variables affect only the current users, whereas System variables affect all users.

- To edit the existing PATH, select Edit and add ;[PythonInstallationDir]\Scripts\ at the end of the value. Note that the leading colon (;) is important, as it separates different entries. To add a new value, select New and provide both the name and the value, this time without the colon.

- Start a new command prompt for the changes to take effect.

Verifying installation

To verify that the installation and environment setup were successful, type:

$ pybot --version Robot 2.0 (Python 2.5.1 on cygwin)

To verify that Robot Framework works also with Jython, type:

$ jybot --version Robot 2.2 (Jython 2.2 on java1.6.0_03)

In both cases, the exact version and platform information can, of course, differ from these. On Jython, you may also get some notifications from Jython's package manager upon the first execution.

1.3.4 Uninstallation

If Robot Framework has been installed using a source distribution, it can be uninstalled with command:

python install.py uninstall

If Robot Framework is installed from a binary distribution, it can be uninstalled via the mechanism offered by the operating system. For example, in Windows you simply go to Control Panel > Add/Remove Programs, where Robot Framework is listed under Python.

If uninstallation fails somehow, Robot Framework can be uninstalled by removing the framework code and runner scripts manually.

1.3.5 Upgrading

The procedure when upgrading or downgrading Robot Framework depends on the versions used:

- If you are upgrading from one minor Robot Framework version to another (for example, from 2.0 to 2.0.1), it is safe to install the new version over the old one, unless stated otherwise.

- If you are upgrading from one major Robot Framework version to another (for example, from 2.0 to 2.1), then it is highly recommended to uninstall the old version before the new installation.

- If you are downgrading, the rules are the same as for upgrading.

With source distributions upgrading is easy with command:

python install.py reinstall

1.4 Demonstration

Robot Framework does not currently have a standalone demo, but we plan to add one soon. However, SeleniumLibrary has an easily executable demonstration test suite available. It contains a simple standalone HTTP server and an application that is used as a system under test. The actual test case files and scripts for running the demonstration in different systems are also provided.

The demonstration, as well as instructions for running it, can be downloaded from SeleniumLibrary project page at http://code.google.com/p/robotframework-seleniumlibrary.

2 Creating test data

2.1 Test data syntax

This section covers Robot Framework's overall test data syntax. The following sections will explain how to actually create test cases, test suites and so on.

2.1.1 Files and directories

The hierarchical structure for arranging test cases is built as follows:

- Test cases are created in test case files.

- A test case file automatically creates a test suite containing the test cases in that file.

- A directory containing test case files forms a higher-level test suite. Such a test suite directory has suites created from test case files as its sub test suites.

- A test suite directory can also contain other test suite directories, and this hierarchical structure can be as deeply nested as needed.

- Test suite directories can have a special initialization file.

In addition to this, there are:

- Test libraries containing the lowest-level keywords

- Resource files with variables and higher-level user keywords

- Variable files to provide more flexible ways to create variables than resource files

2.1.2 Supported file formats

Robot Framework test data is defined in tabular format, using either the HTML (hypertext markup language) or TSV (tab-separated values) format. Robot Framework selects a parser for the test data based on the file extension. The extension is case-insensitive, and the recognized extensions are .html, .htm and .xhtml for HTML, and .tsv for TSV.

Source distribution contains both HTML and TSV test data templates and they can also be obtained from Robot Framework's download page.

HTML format

In HTML files, the test data is defined in separate tables (see the example below). Robot Framework recognizes these test data tables based on the text in their first cell. Everything outside recognized tables is ignored.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library | OperatingSystem | ||

| Variable | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${MESSAGE} | Hello, world! | ||

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| My Test | [Documentation] | Example test | |

| Log | ${MESSAGE} | ||

| My Keyword | /tmp | ||

| Another Test | Should Be Equal | ${MESSAGE} | Hello, world! |

| Keyword | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| My Keyword | [Argument] | ${path} | |

| Directory Should Exist | ${path} |

Test data in HTML files can be edited with whichever editor you prefer, but a graphic editor, where you can actually see the tables, is recommended. There is also a tool called Robot IDE available that is actually designed for editing the test data.

HTML entity references (for example, ä) are supported. Additionally, any encoding can be used, assuming that it is specified in the data file. Normal HTML files must use the META element as in the example below:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">

XHTML files should use the XML preamble as in this example:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="Big5"?>

If no encoding is specified, Robot Framework uses ISO-8859-1 by default.

Note

Before Robot Framework version 1.8.4, the HTML test data was always assumed to be in ASCII format.

TSV format

In a TSV file, all the data is in one large table. Test data tables are recognized from an asterisk (*), followed by a normal table name. Robot Framework ignores any other asterisks in the name, so it can also be prefixed with another asterisk as in the example below. In TSV test data, everything before the first recognized table is ignored in Robot Framework.

| *Setting* | *Value* | *Value* | *Value* |

| Library | OperatingSystem | ||

| *Variable* | *Value* | *Value* | *Value* |

| ${MESSAGE} | Hello, world! | ||

| *Test Case* | *Action* | *Argument* | *Argument* |

| My Test | [Documentation] | Example test | |

| Log | ${MESSAGE} | ||

| My Keyword | /tmp | ||

| Another Test | Should Be Equal | ${MESSAGE} | Hello, world! |

| *Keyword* | *Action* | *Argument* | *Argument* |

| My Keyword | [Argument] | ${path} | |

| Directory Should Exist | ${path} |

You can create and edit TSV files in any spreadsheet program, such as Microsoft Excel. Select the tab-separated format when you save the file and remember to set the file extension to .tsv. The TSV format can be used in Robot Framework's test data for all the same purposes as HTML.

Robot Framework parses TSV data by first splitting all the content into rows and then rows into cells on the basis of the tabular characters. Spreadsheet programs sometimes surround cells with quotes (for example, "my value") and Robot Framework removes them. Possible quotes inside the data are doubled (for example, "my ""quoted"" value") and Robot Framework handles also them. If you are using a spreadsheet program to create TSV data, you do not need to pay attention to that, but if you create data programmatically, you have to add the same quotes as spreadsheets.

2.1.3 Test data tables

Test data is structured in four types of tables listed below. These test data tables are identified by the first cell of the table, and the last column in the table below lists different aliases that can be used as a table name.

| Table name | Used for | Aliases |

|---|---|---|

| Setting table | 2) Defining metadata for test suites

and test cases

|

Setting, Settings, Metadata |

| Variable table | Defining variables that can be used elsewhere in the test data | Variable, Variables |

| Test case table | Creating test cases from available keywords | Test Case, Test Cases |

| Keyword table | Creating user keywords from existing lower-level keywords | Keyword, Keywords, User Keyword, User Keywords |

2.1.4 Rules for parsing the data

Ignored data

When Robot Framework parses the test data, it ignores:

- All tables that do not start with a recognized table name in the first cell

- Everything else on the first row apart from the first cell

- Data outside tables in HTML and data before the first table in TSV

- All empty rows, which means these kinds of rows can be used to make the tables more readable

- All empty cells at the end of rows; you must add a backslash (\) to prevent such cells from being ignored

- All single backslashes (\); they are used as an escape character

- All characters following a hash mark (#), if it is the first character of a cell; this means that hash marks can be used to enter comments in the test data

- All formatting in the HTML test data

When Robot Framework ignores some data, this data is not available in any resulting reports and, additionally, most tools used with Robot Framework also ignore them. To add information that is visible in Robot Framework outputs, or available to, for example, Robot IDE, place it to the documentation or other metadata of test cases or suites, or log with the Log or Comment keywords available from the BuiltIn library.

Escaping

The escape character for the Robot Framework parser is the backslash (\). The escape character can be used as follows:

- To escape special characters so that their literal values are

used:

- \${notvar} means a literal string ${notvar} that looks like a variable

- \\ means a single backslash (for example, C:\\Temp)

- \# means a literal hash (#) mark, even at the beginning of a cell

- To affect the parsing of whitespaces

- To prevent Robot Framework from ignoring empty cells at the end of a row (this requires \ to be in the appropriate cell).

Handling whitespace

Robot Framework handles whitespace, such as spaces, newlines and tabs, the same way as they are handled in HTML. This means that Robot Framework:

- Removes leading and trailing whitespaces in all cells.

- Changes multiple consecutive spaces into single spaces.

- Converts all newlines and tabs into spaces.

To prevent Robot Framework from parsing data according to these rules, a backslash can be used:

- Before leading spaces, for example \ some text

- Between consecutive spaces, for example text \ \ more text

- After trailing spaces, for example some text \ \

- With n to create a newline, for example first line\n2nd line

- With t to create a tab character, for example text\tmore text

- With r to create a carriage return, for example text\rmore text

Dividing test data to several rows

If a keyword requires more arguments than there are columns available, it is not necessary to add more columns. Instead, it is possible to simply have three dots (...) below the original keyword name and continue arguments there. Arguments presented like this are parsed as if they were all in one row.

The same approach works also with settings and variables taking several values. In these cases, the three dots are, of course, placed under the setting or variable name.

Additionally, values of settings that take only one value (mainly documentations) can be split to several columns. These values will be then catenated together with spaces when the test data is parsed.

All these syntaxes are illustrated in the following examples. The first three tables show tables where test data has not been split, and the following three illustrate how fewer columns are needed after splitting the data to several rows.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Default Tags | tag-1 | tag-2 | tag-3 | tag-4 | tag-5 | tag-6 |

| Variable | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @{LIST} | this | list | has | quite | many | items |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Arg | Arg | Arg | Arg | Arg | Arg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | [Documentation] | Documentation for this test case. This can get quite long... | ||||||

| [Tags] | t-1 | t-2 | t-3 | t-4 | t-5 | |||

| Do X | one | two | three | four | five | six | ||

| ${var} = | Get X | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Tags | tag-1 | tag-2 | tag-3 |

| ... | tag-4 | tag-5 | tag-6 |

| Variable | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| @{LIST} | this | list | has |

| ... | quite | many | items |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | [Documentation] | Documentation | for this | test case. |

| ... | This can get | quite | long... | |

| [Tags] | t-1 | t-2 | t-3 | |

| ... | t-4 | t-5 | ||

| Do X | one | two | three | |

| ... | four | five | six | |

| ${var} = | Get X | 1 | 2 | |

| ... | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| ... | 6 |

2.2 Creating test cases

This section describes the overall test case syntax. Organizing test cases into test suites using test case files and test suite directories is discussed in the next section.

2.2.1 Test case syntax

Basic syntax

Test cases are constructed in test case tables from the available keywords. Keywords can be imported from test libraries or resource files, or created in the keyword table of the test case file itself.

The first column in the test case table contains test case names. A test case starts from the row with something in this column and continues to the next test case name or to the end of the table. It is an error to have something between the table headers and the first test.

The second column normally has keyword names. An exception to this rule is setting variables from keyword return values, when the second and possibly also the subsequent columns contain variable names and a keyword name is located after them. In either case, columns after the keyword name contain possible arguments to the specified keyword.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid Login | Open Login Page | ||

| Input Name | demo | ||

| Input Password | mode | ||

| Submit Credentials | |||

| Welcome Page Should Be Open | |||

| Setting Variables | Do Something | first argument | second argument |

| ${value} = | Get Some Value | ||

| Should Be Equal | ${value} | Expected value |

Workflow tests vs. data-driven tests

In general, there are two kinds of test cases. So called workflow tests, such as the Valid Login test above, are constructed from several keywords. Their normal structure is that first the system is taken into the initial state (Open Login Page), then something is done to the system (Input Name, Input Password, Submit Credentials), and finally it is verified that the system behaved as expected (Welcome Page Should Be Open).

Another type of tests are data-driven test cases that contain only one higher-level keyword, normally created as user keywords. These kinds of tests are very useful when there is a need to test the same workflow with different input or output data, as the examples below demonstrate.

| Test Case | Action | User Name | Password |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invalid User Name | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | invalid | mode |

| Invalid Password | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | demo | invalid |

| Invalid User Name And Password | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | invalid | whatever |

| Empty User Name | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | mode | |

| Empty Password | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | demo | \ |

| Empty User Name And Password | Login With Invalid Credentials Should Fail | \ |

Note that in the example above, column headers have been changed to match the data. This is possible, because on the first row other cells except the first one are ignored. Additionally, backslash is used for escaping empty cells at the end of the table.

Settings in the Test Case table

Test cases can also have their own settings. Setting names are always in the second column, where keywords normally are, and their values are in the subsequent columns. Setting names have square brackets around them to distinguish them from keywords. The available settings are listed below and explained later in this section.

- [Documentation]

- Used for specifying a test case documentation.

- [Tags]

- Used for tagging test cases.

- [Setup], [Teardown]

- Specify test setup and teardown. Have also synonyms [Precondition] and [Postcondition], respectively.

- [Timeout]

- Used for setting a test case timeout. Timeouts are discussed in their own section.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test With Settings | [Documentation] | Another dummy test | |

| [Tags] | dummy | owner-johndoe | |

| Log | Hello, world! |

2.2.2 Test case name and documentation

The test case name comes directly from the Test Case table: it is exactly what is entered into the test case column. Test cases in one test suite should have unique names. Pertaining to this, you can also use the automatic variable ${TEST_NAME} within the test itself to refer to the test name. It is available whenever a test is being executed, including all user keywords, as well as the test setup and the test teardown.

The [Documentation] setting allows you to set a free documentation for a test case. That text is shown in the command line output, as well as the resulting test logs and test reports. If the documentation is long, it can be split into several cells that are catenated together with spaces. It is possible to use simple HTML formatting and even variables can be used.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | [Documentation] | Simple documentation | |

| No Operation | |||

| Splitting | [Documentation] | This documentation is a bit longer and | it has been split into several columns. |

| No Operation | |||

| Formatting | [Documentation] | *This is bold*, _this italic_ and | here is a link: http://robotframework.org |

| No Operation | |||

| Variables | [Documentation] | Executed at ${HOST} by ${USER} | |

| No Operation |

It is important that test cases have clear and descriptive names, and in that case they normally do not need any documentation. If the logic of the test case needs documenting, it is often a sign that keywords in the test case need better names and they are to be enhanced, instead of adding extra documentation. Finally, metadata, such as the environment and user information in the last example above, is often better specified using tags.

2.2.3 Tagging test cases

Using tags in Robot Framework is a simple, yet powerful mechanism for classifying test cases. Tags are free text and they can be used at least for the following purposes:

- Tags are shown in test reports, logs and, of course, in the test data, so they provide metadata to test cases.

- Statistics about test cases (total, passed, failed are automatically collected based on tags.

- With tags, you can include or exclude test cases to be executed.

- With tags, you can specify which test cases are considered critical.

In this section it is only explained how to set tags for test cases, and different ways to do it are listed below. These approaches can naturally be used together.

- Force Tags in the Setting table

- All test cases in a test case file with this setting always get specified tags. If it is used in the test suite initialization file, all test cases in sub test suites get these tags.

- Default Tags in the Setting table

- Test cases that do not have a [Tags] setting of their own get these tags. If it used in the test suite initialization file, it is interpreted as a default value for Default Tags in lower-level test suites.

- [Tags] in the Test Case table

- A test case always gets these tags. Additionally, it does not get the possible tags specified with Default Tags.

- --settag command line option

- All executed test cases get tags set with this option in addition to tags they got elsewhere. This option is only available in Robot Framework version 1.8.3 and newer.

Tags are free text, but they are normalized so that they are converted to lowercase and all spaces are removed. If a test case gets the same tag several times, other occurrences than the first one are removed. Tags can be created using variables, assuming that those variables exist.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Tags | req-42 | ||

| Default Tags | owner-john | smoke |

| Variable | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${HOST} | 10.0.1.42 |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| No own tags | [Documentation] | This test has tags | owner-john, smoke, req-42 |

| No Operation | |||

| With own tags | [Documentation] | This test has tags | not_ready, owner-mrx, req-42 |

| [Tags] | owner-mrx | not_ready | |

| No Operation | |||

| Own tags with variables | [Documentation] | This test has tags | host-10.0.1.42, req-42 |

| [Tags] | host-${HOST} | ||

| No Operation | |||

| Empty own tags | [Documentation] | This test has tags | req-42 |

| [Tags] | |||

| No Operation |

2.2.4 Test setup and teardown

Robot Framework has similar test setup and teardown functions as many other test automation frameworks. In short, a test setup is something that is executed before a test case and a test teardown is executed after a test case. What makes a test teardown special is that it is executed also when a test case fails, so it can be used for clean-up activities that must be done regardless of the test case status. Both a setup and a teardown can also easily be specified for all test cases in a test suite, so using them avoids repetition.

In Robot Framework, a test setup or teardown is just a normal keyword with possible arguments. It can either be a keyword from a library or a higher-level user keyword.

The easiest way to specify a setup or a teardown for test cases in a test suite is using the Test Setup and Test Teardown settings in the Setting table. Individual test cases can also have their own setup or teardown. They are defined with the [Setup] or [Teardown] settings in the test case table and they override possible Test Setup and Test Teardown settings. Having no keyword after a [Setup] or [Teardown] setting means having no setup or teardown.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Setup | Open Application | App A | |

| Test Teardown | Close Application |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default values | [Documentation] | Setup and teardown | from setting table |

| Do Something | |||

| Overridden setup | [Documentation] | Own setup, teardown | from setting table |

| [Setup] | Open Application | App B | |

| Do Something | |||

| No teardown | [Documentation] | Default setup, no | teardown at all |

| Do Something | |||

| [Teardown] | |||

| Using variables | [Documentation] | Setup and teardown | given as variables |

| [Setup] | ${SETUP} | ||

| Do Something | |||

| [Teardown] | ${TEARDOWN} |

Often when creating use-case-like test cases, the terms precondition and postcondition are preferred over the terms setup and teardown. Robot Framework supports also this terminology, so that a precondition is a synonym to a setup and a postcondition to a teardown.

| Test Setup | Test Precondition |

| Test Teardown | Test Postcondition |

| [Setup] | [Precondition] |

| [Teardown] | [Postcondition] |

The name of the keyword to be executed as a setup or a teardown can be a variable. This facilitates having different setups or teardowns in different environments by giving the keyword name as a variable from the command line.

Note

Test suites can have a setup and teardown of their own. A suite setup is executed before any test cases or sub test suites in that test suite, and similarly a suite teardown is executed after them.

2.3 Creating test suites

Robot Framework test cases are created in test case files, which can be organized into directories. These files and directories create a hierarchical test suite structure.

2.3.1 Test case files

Robot Framework test cases are created using test case tables in test case files. Such a file automatically creates a test suite from all the test cases it contains. There is no upper limit for how many test cases there can be, but it is recommended to have less than ten, unless the data-driven approach is used, where one test case consists of only one high-level keyword.

The following settings in the Setting table can be used to customize the test suite:

- Documentation

- Used for specifying a test suite documentation

- Meta: <name>

- Used for setting free test suite metadata.

- Suite Setup, Suite Teardown

- Specify suite setup and teardown. Have also synonyms Suite Precondition and Suite Postcondition, respectively.

2.3.2 Test suite directories

Test case files can be organized into directories, and these directories create higher-level test suites. A test suite created from a directory cannot have any test cases directly, but it contains other test suites with test cases, instead. These directories can then be placed into other directories creating an even higher-level suite. There are no limits for the structure, so test cases can be organized as needed.

When a test directory is executed, the files and directories it contains are processed recursively as follows:

- Files and folders with names starting with a dot (.) or an underscore (_) are ignored.

- Files with names not having the .html, .xhtml, .htm or .tsv extension (case-insensitive) are ignored.

- Directories with the name CVS (case-sensitive) are ignored.

- Other files and directories are processed.

The files and directories that are processed are expected to be test case files and test directories, respectively, but if they do not contain any test cases, they are silently ignored (a message is written to the syslog) and the processing continues.

Initialization files

A test suite created from a directory can have the same settings (Documentation, Meta: <name>, Suite Setup, Suite Teardown) as a test case created from a file. Because a directory alone cannot have that kind of information, they must be placed into a special initialization file.

Initialization files have the same structure as test case files, except that they cannot have test case tables, and the overall syntax used in them is the same as in other test data files. An initialization file name must always be of the format __init__.extension, where the extension is the same as normally for test data files (for example, __init__.html or __init__.tsv). The name format is borrowed from Python, where files named in this manner denote that a directory is a module.

The main usage of initialization files is setting test-suite-related settings, but setting test-case-related settings is also possible. However, only Force Tags is generally useful, because others are only default values for the same settings in lower-level files, and even they are default values for the settings in the Test Case table.

| Setting | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation | Example suite | |

| Suite Setup | Do Something | ${MESSAGE} |

| Force Tags | example | |

| Library | SomeLibrary |

| Variable | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ${MESSAGE} | Hello, world! |

| Keyword | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do Something | [Arguments] | ${arg} | |

| Log | ${arg} |

Note that variables and keywords created in initialization files are not available elsewhere. If there is a need to share them, for example, with lower-level test suites, resource files must be used.

2.3.3 Test suite name and documentation

The test suite name is got directly from the file or directory name, but a possible file extension is ignored. The name is created so that underscores are replaced with spaces, words in camelCaseFormat separated, and first letters of all words capitalized. For example, some_tests.html becomes Some Tests and MyTestDir becomes My Test Dir.

The documentation for a test suite is set using the Documentation setting in the Setting table. It can be used in test case files or, with higher-level suites, in test suite initialization files. Test suite documentation has exactly the same characteristics regarding to where it is shown and how it can be created as test case documentation.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Documentation | An example test suite | documentation with | *some* _formatting_. |

| ... | See test documentation | for more documentation | examples. |

Both the name and documentation of the top-level test suite can be overridden in test execution. This can be done with the command line options --name and --doc, respectively, as explained in section Setting metadata.

2.3.4 Free test suite metadata

Test suites can also have other metadata than the documentation. This metadata is defined in the Setting table using the Meta: <name> setting, where <name> is a freely selected metadata name. For example, Meta: Version adds the version metadata for a test suite. Metadata set in this manner is shown in test reports and logs.

The value for the metadata is located in the column after the name. It is handled similarly as documentations, which means that it can be split into several cells (joined together with spaces), simple HTML formatting works and even variables can be used.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta: Version | 2.0 | ||

| Meta: More Info | For more information | about *Robot Framework* | see http://robotframework.org |

| Meta: Executed At | ${HOST} |

For top-level test suites, it is possible to set metadata also with the --metadata command line option. This is discussed in more detail in section Setting metadata.

2.3.5 Suite setup and teardown

Not only test cases but also test suites can have a setup and a teardown. A suite setup is executed before running any of the suite's test cases or child test suites, and a test teardown is executed after them. All test suites can have a setup and a teardown; with suites created from a directory they must be specified in a test suite initialization file.

Similarly as with test cases, a suite setup and teardown are keywords that may take arguments. They are defined in the Setting table with Suite Setup and Suite Teardown settings, respectively. They also have similar synonyms, Suite Precondition and Suite Postcondition, as a test case setup and teardown have. Keyword names and possible arguments are located in the columns after the setting name.

If a suite setup fails, all test cases in it and its child test suites are immediately assigned a fail status and they are not actually executed. This makes suite setups ideal for checking preconditions that must be met before running test cases is possible.

A suite teardown is normally used for cleaning up after all the test cases have been executed. It is executed even if the setup of the same suite fails. If the suite teardown fails, all test cases in the suite are marked failed, regardless of their original execution status.

The name of the keyword to be executed as a setup or a teardown can be a variable. This facilitates having different setups or teardowns in different environments by giving the keyword name as a variable from the command line.

2.4 Using test libraries

Test libraries contain those lowest-level keywords, often called library keywords, which actually interact with the system under test. All test cases always use keywords from some library, often through higher-level user keywords. This section explains how to take test libraries into use and how to use the keywords they provide. Creating test libraries is described in a separate section.

2.4.1 Taking test libraries into use

Instructions for taking test libraries into use are given in the subsections below.

Using Library setting

Test libraries are normally imported using the Library setting in the Setting table and having the library name in the subsequent column. The library name is case-sensitive (it is the name of the module or class implementing the library and must be exactly correct), but any spaces in it are ignored. With Python libraries in modules or Java libraries in packages, the full name including the module or package name must be used. In those cases where the library needs arguments, they are listed in the columns after the library name. Both the library name and arguments can be set using variables.

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library | OperatingSystem | ||

| Library | com.company.TestLib | ||

| Library | MyLibrary | arg1 | arg2 |

| Library | ${LIBRARY} |

It is possible to import test libraries in test case files, resource files and test suite initialization files. In all these cases, all the keywords in the imported library are available in that file. With resource files, those keywords are also available in other files using them.

Using Import Library keyword

Another possibility to take a test library into use is using the keyword Import Library from the BuiltIn library. This keyword takes the library name and possible arguments similarly as the Library setting. Keywords from the imported library are available in the test suite where the Import Library keyword was used. This approach is useful in cases where the library is not available when the test execution starts and only some other keywords make it available.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | Do Something | |||

| Import Library | MyLibrary | arg1 | arg2 | |

| KW From Mylibrary |

Library search path

Robot Framework can import a library only if the library class or module can be found from the library search path. Basically, this means that the library code and all its possible dependencies must be in PYTHONPATH or, when running tests on Jython, in a CLASSPATH. Setting the library search path is explained in a section of its own, and well-developed libraries either do that automatically or have clear instructions on how to do it.

2.4.2 Setting custom name to test library

The library name is shown in test logs before keyword names, and if multiple keywords have the same name, they must be used so that the keyword name is prefixed with the library name. The library name is got normally from the module or class name implementing it, but there are some situations where changing it is desirable:

- There is a need to import the same library several times with different arguments. This is not possible otherwise.

- The library name is inconveniently long. This can happen, for example, if a Java library has a long package name.

- You want to use variables to import different libraries in different environments, but refer to them with the same name.

- The library name is misleading or otherwise poor. In this case, changing the actual name is, of course, a better solution.

The basic syntax for specifying the new name is having the text WITH NAME (case-insensitive) after the library name and then having the new name in the next cell. The specified name is shown in logs and must be used in the test data when using keywords' full name (LibraryName.Keyword Name).

| Setting | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library | com.company.TestLib | WITH NAME | TestLib |

| Library | ${LIBRARY} | WITH NAME | MyName |

Possible arguments to the library are placed into cells between the original library name and the WITH NAME text. The following example illustrates how the same library can be imported several times with different arguments:

| Setting | Value | Value | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library | SomeLibrary | localhost | 1234 | WITH NAME | LocalLib |

| Library | SomeLibrary | server.domain | 8080 | WITH NAME | RemoteLib |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| My Test | LocalLib.Some Keyword | some arg | second arg |

| RemoteLib.Some Keyword | another arg | whatever | |

| LocalLib.Another Keyword |

Setting a custom name to a test library works both when importing a library in the Setting table and when using the Import Library keyword.

2.4.3 Standard libraries

Some test libraries are distributed with Robot Framework and these libraries are called standard libraries. These are the available standard libraries:

The BuiltIn library is special, because it is taken into use automatically and thus its keywords are always available. Other standard libraries need to be imported in the same way as any other libraries, but there is no need to install them. Additionally, they work when running tests both with Python and Jython (with the Screenshot library as an exception).

New standard libraries can, and will, be added in the future. If you have an idea for a new standard library, or even have one that could be incorporated immediately, please contact Robot Framework developers. In general, a library is a good candidate to be added into standard libraries if it is generic, works on both Python and Jython without any external dependencies, and is adequately tested and documented.

BuiltIn library

The BuiltIn library provides a set of generic keywords needed often. The provided keywords allow functions for verifications (for example, Should Be Equal), conversions (for example, Convert To Integer) and for various other purposes (for example, Log and Sleep).

The names of the keywords in the BuiltIn library have been renamed for Robot Framework version 1.8. All the old keywords still work, but the long names (the names visible in log files) of the keywords that are deprecated begin with DeprecatedBuiltIn. (for example, DeprecatedBuiltIn.Equals).

For more information, see the BuiltIn library documentation.

OperatingSystem library

The OperatingSystem library enables various operating-system-related tasks to be performed in the system running Robot Framework. It can, among other things, execute commands (for example, Run) and check whether files exist or not (for example, File Should Exist). The idea of the library is to wrap all relevant functions from the standard Python modules os, os.path and shutil, but other related functions can also be added.

The names of the keywords in the OperatingSystem library have been renamed for Robot Framework version 1.8. All the old keywords still work, but the long names (names visible in log files) of the keywords that are deprecated begin with DeprecatedOperatingSystem. (for example, DeprecatedOperatingSystem.Fail Unless File Empty).

For more information, see the OperatingSystem library documentation.

Telnet library

The Telnet library enables testing over a Telnet connection. It has functions for logging into a Telnet server, running commands on the server and returning the output. The Telnet library extends Python's own telnetlib module and it supports several simultaneous connections.

For more information, see the Telnet library documentation.

Collections library

The Collections library provides a set of keywords for handling Python's standard list and dictionary data structures. For more information about lists and dictionaries, see Python Library Reference . The provided keywords allow functions for creating dictionaries (Create Dictionary), modifying lists and dictionaries (for example, Append To List), and checking the equality of lists and dictionaries (for example, Dictionaries Should Be Equal).

For more information, see the Collections library documentation.

Screenshot library

The Screenshot library provides a way to capture and store screenshots of the whole desktop. This library is implemented with Java AWT APIs, so it can be used only when running Robot Framework with Jython.

For more information, see the Screenshot library documentation.

2.4.4 External libraries

Any test library that is not one of the standard libraries is, by definition, an external library. Robot Framework developers provide some generic libraries, such as SeleniumLibrary, which are not packaged with the framework itself, because they require external dependencies. Generic libraries can also be provided by other parties, and most teams have also some custom libraries only for themselves.

Different external libraries can have a totally different mechanism for installing and introducing them. Quite often they also require some other dependencies to be installed separately. All libraries should have clear instructions on this and preferably automate the installation.

2.5 Variables

2.5.1 Introduction

Variables are an integral feature of Robot Framework, and they can be used in most places in test data. Most commonly, they are used in arguments for keywords in test case tables and keyword tables, but also all settings allow variables in their values. A normal keyword name cannot be specified with a variable, but the BuiltIn keyword Run Keyword can be used to get the same effect.

Robot Framework itself has two kinds of variables, scalars and lists, and they have the syntaxes ${VARIABLE} and @{VARIABLE}, respectively. In addition to this, environment variables can be used directly with the syntax %{VARIABLE}.

The use of variables is recommended in the following cases:

- When strings change often in the test data. With variables you only need to make these changes in one place.

- When creating system-independent and operating-system-independent test data. Using variables instead of hard-coded strings eases that considerably (for example, ${RESOURCES} instead of c:\resources, or ${HOST} instead of 10.0.0.1:8080). Because variables can be set from the command line when tests are started, changing system-specific variables is easy (for example, --variable HOST:192.168.0.12 --variable RESOURCES:/opt/resources). This also facilitates localization testing, which often involves running the same tests with different strings.

- When there is a need to have objects other than strings as arguments for keywords.

- When different keywords, even in different test libraries, need to communicate. You can assign a return value from one keyword to a variable and give that as an argument to another.

- When values in the test data are long or otherwise complicated. For example, ${URL} is shorter than http://long.domain.name:8080/path/to/service?foo=1&bar=2&zap=42.

If a nonexistent variable is used in the test data, the keyword using it fails. If the same syntax that is used for variables is needed as a literal string, it must be escaped with a backslash as in \${NAME}.

2.5.2 Variable types

Different variable types are briefly described in this section. The creation and usage of variables is described in more detail in the following subsections.

Robot Framework variables, similarly as keywords, are case-insensitive, and also spaces and underscores are ignored. However, it is recommended to use all capital letters with global variables (for example, ${PATH} or ${TWO_WORDS}) and small letters with variables that are only available in certain test cases or user keywords (for example, ${my_var} or ${myVar}). What is even more important is that cases are used consistently.

Unlike in some programming languages where similar variable syntax is used, curly braces ("{" and "}") are mandatory in Robot Framework test data. Basically, variable names can have any characters between the curly braces. However, using only alphabetic characters (from a to z), numbers (from 0 to 9), underscore and space is recommended, and it is even a requirement for using extended variable syntax.

Scalar variables

When scalar variables are used in the test data, they are replaced with the value they are assigned to. While scalar variables are most commonly used for simple strings, you can assign any objects, including lists, to them. The scalar variable syntax, for example ${NAME}, should be familiar to most users, as it is also used, for example, in shell scripts and Perl.

The example below illustrates the usage of scalar variables. Assuming that the variables ${GREET} and ${NAME} are available and assigned to strings Hello and world, respectively, both the example test cases are equivalent.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strings | Log | Hello | |

| Log | Hello, world!! | ||

| Variables | Log | ${GREET} | |

| Log | ${GREET}, ${NAME}!! |

When a scalar variable is used as the only value in a test data cell, the scalar variable is replaced with the value it has. The value may be any object. When a scalar variable is used in a test data cell with anything else (constant strings or other variables), its value is first converted into a string and then catenated to whatever is in that cell. Converting the value into a string means that the object's method =__str__ (in Python) or toString (in Java) is called.

The example below demonstrates the difference between having a variable in a cell alone or with other content. First, let us assume that we have a variable ${STR} set to a string Hello, world! and ${OBJ} set to an instance of the following Java object:

public class MyObj {

public String toString() {

return "Hi, tellus!";

}

}

With these two variables set, we then have the following test data:

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objects | KW 1 | ${STR} | |

| KW 2 | ${OBJ} | ||

| KW 3 | I said "${STR}" | ||

| KW 4 | You said "${OBJ}" |

Finally, when this test data is executed, different keywords receive the arguments as explained below:

- KW 1 gets a string Hello, world!

- KW 2 gets an object stored to variable ${OBJ}

- KW 3 gets a string I said "Hello, world!"

- KW 4 gets a string You said "Hi, tellus!"

List variables

List variables are compound variables that can have several values assigned to them. In short, they are always lists and can contain an unlimited number of entries (also empty lists are possible). The main benefit of list variables is that they allow you to assign a name for a larger data set. While list variables normally contain only strings, other content is also possible.

When you use a list variable in test data, then the cell that contains the variable is replaced with the content of the variable. Thus, if the list variable contains two elements, the cell containing the list variable is turned into two cells with the content of the list variable. Note that cells with list variables should not contain other content. The list variable syntax, @{NAME}, is borrowed from Perl.

Assuming that the list variable @{USER} is set to the value ['robot','secret'], the following two test cases are equivalent.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strings | Login | robot | secret |

| List Variable | Login | @{USER} |

It is also possible to access a certain value from the list variable with the syntax @{NAME}[i], where "i" is the index of the selected value. Indexes start from zero, and trying to access a value with too large an index causes an error. List items accessed in this manner can be used similarly as scalar variables.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strings | Login | robot | secret |

| Title Should Be | Welcome robot! | ||

| List Variable | Login | @{USER} | |

| Title Should Be | Welcome @{USER}[0]! |

Environment variables

Robot Framework allows using environment variables in the test data using the syntax %{ENV_VAR_NAME}. They are limited to string values.

Environment variables set in the system before the test execution are available during it, and it is possible to create new ones with the keyword Set Environment Variable or delete existing ones with the keyword Delete Environment Variable, both available in the OperatingSystem library. Because environment variables are global, environment variables set in one test case can be used in other test cases executed after it. However, changes to environment variables are not effective after the test execution.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Env Variables | Log | Current user: %{USER} | |

| Run | %{JAVA_HOME}${/}javac |

2.5.3 Creating variables

Variables can spring into existence from different sources as described in the subsections below.

Variable table

The most common source for variables are Variable tables in test case files and resource files. Variable tables are convenient, because they allow creating variables in the same place as the rest of the test data, and the needed syntax is very simple. Their main disadvantage is that they only enable assigning variables into strings or a list of strings. If other value types are needed, variable files are probably a better option.

Creating scalar variables

The simplest possible variable assignment is setting a string into a scalar variable. This is done by giving the variable name (including ${}) in the first column of the Variable table and the value in the second one. If the second column is empty, an empty string is set as a value. Also an already defined variable can be used in the value.

| Variable | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ${NAME} | Robot Framework | |

| ${VERSION} | 2.0 | |

| ${EMPTY} | ||

| ${ROBOT} | ${NAME} ${VERSION} |

Since Robot Framework version 1.8, it is possible, but not obligatory, to use the equals sign = after the variable name to make assigning variables slightly more explicit.

| Variable | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ${NAME} = | Robot Framework | |

| ${VERSION} = | 2.0 |

Creating list variables

Creating list variables is as easy as creating scalar variables. Again, the variable name is in the first column of the Variable table and values in the subsequent columns. A list variable can have any number of values, starting from zero, and if many values are needed, they can be split into several rows.

| Variable | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| @{NAMES} | Matti | Teppo | |

| @{EMPTY} | |||

| @{NAMES2} | @{NAMES} | @{EMPTY} | Seppo |

| @{MANY} | one | two | three |

| ... | four | five | six |

| ... | seven |

Variable file

Variable files are the most powerful mechanism for creating different kind of variables. It is possible to assign variables to any object using them, and they also enable creating variables dynamically. The variable file syntax and taking variable files into use is explained in section Resource and variable files.

Setting variables in command line

Variables can be set from the command line either individually with the --variable option or using a variable file with the --variablefile option. Variables set from the command line are globally available for all executed test data files, and they also override variables with the same names in the Variable table and in the imported variable files.

The syntax for setting individual variables is --variable name:value, where name is the name of the variable without ${} and value is its value. Several variables can be set by using this option several times. Only scalar variables can be set from the command line and they can only get string values. Many special characters are difficult or impossible to represent in the command line, but they can be escaped with the --escape option.

--variable EXAMPLE:value

--variable HOST:localhost:7272 --variable USER:robot

--variable ESCAPED:Qquotes_and_spacesQ --escape quot:Q --escape space:_

In the examples above, variables are set so that

- ${EXAMPLE} gets the value value

- ${HOST} and ${USER} get the values localhost:7272 and robot

- ${ESCAPED} gets the value "quotes and spaces"

Variable files are given from the command line using the syntax --variablefile path/to/variables.py. Which variables actually are created depends on which variables there are in the referenced variable file. If both variable files and individual variables are given from the command line, the latter override possible variables with the same name in the variable files.

Return values from keywords

Return values from keywords can also be set into variables. This allows communication between different keywords even in different test libraries. The syntax for a simple case is illustrated in the example below:

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Returning | ${x} = | Get X | an argument |

| Log | We got ${x}! |

In the example above, the value returned by the Get X keyword is first set into the variable ${x} and then used by the Log keyword. This syntax works in all cases where a keywords returns something, and the variable is set to whatever value returned by the keyword. Having the equals sign = after the variable name is not obligatory, but recommended, because it makes the assignment more explicit.

If a keyword returns a list, it is also possible to set it into several scalar variables or into a list variable. This is possible with keywords returning Python lists or tuples or, from Robot Framework version 1.8.6 onwards, with Java keywords returning an array. In the future, it is possible to add support also for other iterables, if needed.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return Multiple | ${scalar} = | Get 3 | ||

| ${a} | ${b} | ${c}= | Get 3 | |

| ${first} | @{rest} = | Get 3 | ||

| @{list} = | Get 3 |

Assuming that the keyword Get 3 returns a list [1, 2, 3], the following variables are created:

- ${scalar} with the value [1, 2, 3]

- ${a}, ${b} and ${c} with the values 1, 2, and 3, respectively

- ${first} with the value 1, and @{rest} with the value [2, 3]

- @{list} with the value [1, 2, 3]

Variables set in this manner are otherwise similar to any other variables, but they are available only within the scope of the test case or keyword where they are created. Thus it is not possible, for example, to set a variable in one test case and use it in another. This is because, in general, automated test cases should not depend on each other, and accidentally setting a variable that is used elsewhere could cause hard-to-debug errors. If there is a genuine need for setting a variable in one test case and using it in another, use the Set Suite Variable or Set Global Variable keywords available from the BuiltIn library.

Variable scopes

Depending on where and how they are created, variables can have a global, test suite, test case or user keyword scope.

Global scope

Global variables are available everywhere in the test data. These variables are normally set from the command line with the --variable and --variablefile options. Additionally, it is possible to create new global variables or change the existing ones with the BuiltIn keyword Set Global Variable anywhere in the test data.

Global variables override variables defined in Variable tables or in imported variable files. Variables set locally override even global variables, but only in that local scope. It is recommended to use capital letters with global variables.

Test suite scope

Variables with the test suite scope are available anywhere in the test suite where they are defined or imported. They can be created in Variable tables, imported from variable files using the Variables setting in the Setting table, or set with the BuiltIn keyword Set Suite Variable anywhere in that test suite.

The test suite scope is not recursive, which means that variables available in a higher-level test suite are not available in lower-level suites. If necessary, resource and variable files can be used for sharing variables.

Since these variables can be considered global in the test suite where they are used, it is recommended to use capital letters also with them.

Test case scope

Variables created in test cases from the return values of keywords have a test case scope and they are available only in that test case. Another possibility to create them is using the BuiltIn keyword Set Test Variable anywhere in that particular test case. Test case variables are local and should use lower-case letters.

User keyword scope

User keywords get their own variables from arguments passed to them and return values from the keywords they use. Also these variables are local and should use lower-case letters.

2.5.4 Built-in variables

Robot Framework provides some built-in variables that are available automatically.

Operating-system variables

Built-in variables related to the operating system ease making the test data operating-system-agnostic.

| Variable | Explanation |

|---|---|

| ${CURDIR} | An absolute path to the directory where the test data file is located. This variable is case-sensitive. |

| ${TEMPDIR} | An absolute path to the system temporary directory. In UNIX-like systems this is typically /tmp, and in Windows c:\Documents and Settings\<user>\Local Settings\Temp. |

| ${/} | The system directory path separator. / in UNIX-like systems, \ in Windows. |

| ${:} | The system path element separator. : in UNIX-like systems and ; in Windows. |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example | Create File | ${CURDIR}${/}input.data | Some text here |

| Set Environment Variable | CLASSPATH | ${TEMPDIR}${:}${TEMPDIR}${/}foo.jar |

Number variables

The variable syntax can be used for creating both integers and floating point numbers, as illustrated in the example below. This is useful when a keyword expects to get a real number as an argument.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example 1A | Connect | example.com | 80 | # Connect gets two strings as arguments |

| Example 1B | Connect | example.com | ${80} | # Connect gets a string and an integer |

| Example 2 | Do X | ${3.14} | ${-1e-4} | # Do X gets floating point numbers 3.14 and -0.0001 |

Boolean and None/null variables

Also Boolean values and Python None and Java null can be created using the variable syntax similarly as numbers.

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean | Set Status | ${true} | # Set Status gets Boolean true as an argument | |

| Create Y | something | ${false} | # Create Y gets a string and Boolean false | |

| None | Do XYZ | ${None} | # Do XYZ gets Python None as an argument | |

| Null | ${ret} = | Get Value | arg | # Checking that Get Value returns Java null |

| Should Be Equal | ${ret} | ${null} |

These variables are case-insensitive, so for example ${True} and ${true} are equivalent. Additionally, ${None} and ${null} are synonyms, because when running tests on the Jython interpreter, Jython automatically converts None and null to the correct format when necessary.

Automatic variables

Some automatic variables can also be used in the test data. These variables can have different values during the test execution and some of them are not even available all the time.

| Variable | Explanation | Available |

|---|---|---|

| ${TEST_NAME} | The name of the current test case. | Test case |

| @{TEST_TAGS} | Contains the tags of the current test case in alphabetical order. | Test case |

| ${TEST_STATUS} | The status of the current test case, either PASS or FAIL. | Test teardown |

| ${TEST_MESSSAGE} | The possible error message of the current test case. | Test teardown |

| ${PREV_TEST_NAME} | The name of the previous test case, or an empty string if no tests have been executed yet. | Everywhere |

| ${PREV_TEST_STATUS} | The status of the previous test case: either PASS, FAIL or an empty string when no tests have been executed. | Everywhere |

| ${PREV_TEST_MESSSAGE} | The possible error message of the previous test case. | Everywhere |

| ${SUITE_NAME} | The full name of the current test suite. | Everywhere |

| ${SUITE_STATUS} | The status of the current test case, either PASS or FAIL. | Suite teardown |

| ${SUITE_MESSAGE} | The full message of the current test suite, including statistics. | Suite teardown |

| ${OUTPUT_FILE} | An absolute path to the current output file. Has different values during execution when outputs are split. | Everywhere |

| ${LOG_FILE} | An absolute path to the current log file or NONE when no log file is created. Has different values during execution when outputs are split. | Everywhere |

| ${REPORT_FILE} | An absolute path to the report file or NONE when no report is created. | Everywhere |

| ${SUMMARY_FILE} | An absolute path to the summary file or NONE when no summary is created. | Everywhere |

| ${DEBUG_FILE} | An absolute path to the debug file or NONE when no debug file is created. | Everywhere |

| ${OUTPUT_DIR} | An absolute path to the output directory. | Everywhere |

2.5.5 Advanced variable features

There are also some advanced variable features, described in this section.

Extended variable syntax

Extended variable syntax can be used with objects set into scalar variables. This allows accessing the attributes of the object (for example, ${obj.name} or ${obj.some_attr}), and even calling its methods (for example, ${obj.get_name()} or ${obj.getSomething('arg')}.

Extended variable syntax is a powerful feature, but it should be used with care. Accessing attributes is normally not a problem, on the contrary, as one variable with an object having several attributes is often better than having several variables. On the other hand, calling methods, especially when they are used with arguments, can make the test data complicated. If that happens, it is recommended to move the code into a test library.

The most common usages of extended variable syntax are illustrated in the example below. First assume that we have the following variable file and test case:

class MyObject:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def greet(self, who):

return '%s says hello to %s' % (self.name, who)

def __str__(self):

return self.name

OBJECT = MyObject('Robot')

DICTIONARY = { 1: 'one', 2: 'two', 3: 'three'}

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example | KW 1 | ${OBJECT.name} | |

| KW 2 | ${OBJECT.greet('Fit')} | ||

| KW 3 | ${DICTIONARY[2]} |

When this test data is executed, the keywords get the arguments as explained below:

- KW 1 gets string Robot

- KW 2 gets string Robot says hello to Fit

- KW 3 gets string two

The extended variable syntax is evaluated in the following order:

- The variable is searched using the full variable name. The extended variable syntax is evaluated only, if no matching variable is found.

- The real name of the base variable is created. The body of the name consists of all the characters after ${ until the first occurrence of a non-alphanumeric character or a space (for example, OBJECT in ${OBJECT.name} and DICTIONARY in ${DICTIONARY[2]}).

- A variable matching the body is searched. If there is no match, an exception is raised and the test case fails.

- The expression inside the curly brackets is evaluated as a Python expression, so the base variable name is replaced with its value. If the evaluation fails because of an invalid syntax or that the queried attribute does not exist, an exception is raised and the test fails.

- The whole extended variable is replaced with the value returned from the evaluation.

If the object that is used is implemented with Java, the extended variable syntax allows you to access attributes using so-called bean properties. In essence, this means that if you have an object with the getName method set into a variable ${OBJ}, then the syntax ${OBJ.name} is equivalent to, but clearer than ${OBJ.getName()}. Thus the Python object used in the previous example could be replaced with the following Java implementation:

public class MyObject:

private String name;

public MyObject(String name) {

name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public String greet(String who) {

return name + " says hello to " + who;

}

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

Variables inside variables

Variables are allowed also inside variables, and when this syntax is used, variables are resolved from the inside out. For example, if you have a variable ${var${x}}, then ${x} is resolved first. If it has the value name, the final value is then the value of the variable ${varname}. There can be several nested variables, but resolving the outermost fails, if any of them does not exist.

In the example below, Do X gets the value ${JOHN_HOME} or ${JANE_HOME}, depending on if Get Name returns john or jane. If it returns something else, resolving ${${name}_HOME} fails.

| Variable | Value | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ${JOHN_HOME} | /home/john | ||

| ${JANE_HOME} | /home/jane |

| Test Case | Action | Argument | Argument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example | ${name} = | Get Name | |

| Do X | ${${name}_HOME} |

2.6 Creating user keywords